Overcoming addiction

How yoga saved my life

By Rae Delanie PassfieldShaura spent ten years trying to free herself from addiction. Finally, having sought refuge with a Native American tribe, she discovered how recovery and peace could be found through spiritual practice.

Drawing from her own life experience, Shaura now leads the UK’s first yoga for addictions course, guiding those still in the grip of addiction out of darkness one exhale at a time.

This is her story.

Chapter 1: Catalyst

At the delicate age of 16 Shaura packed her bags and left her suburban family home for a flat on a Sheffield council estate. It was a choice that had been a long time coming; having grown up feeling anxious and lost, she was seeking something better, something more. “I always felt lonely as a child. I would often read books to escape into dream worlds,” she says.

This feeling of wanting to escape stayed with Shaura into her teens and was the motivation behind leaving home so young. “I didn’t really know what I was doing here in the world. What was my purpose? What was the point? I thought by leaving I might be able to find out,” Shaura remembers.

“What was my purpose? What was the point?”

Surrounded by people who shared her search for meaning in the world, Shaura immersed herself in this chaotic life. And at first, it was good; it was the peak of the dance scene in 90s Sheffield and living with such carefree exuberance seemed to speak to Shaura’s inner turbulence.

“My journey into freedom did begin with a lot of positive experiences, but it wasn’t long before that began to turn negative,” Shaura says.

This change of tide happened when Shaura, at age 19, lost her newborn child.

“It was an incredibly painful time”

When Shaura’s baby was born with a congenital heart defect, she was told he would not survive. “One of the valves in his heart had not grown and they weren’t able to operate. All I could do was wait for the child to die,” Shaura says.

“It was an incredibly painful time. I was having dreams that my baby was falling asleep and I knew that if he fell to sleep he was going to die. I would wake up on the other side of those dreams very distressed.”

After just five days, Shaura’s baby passed away. She was left heartbroken.

Shaura's boyfriend at the time, a boxer, had recently started to experiment with heroin. She knew this substance could ease her suffering.

“I was in pain, reaching out for understanding, trying to gain meaning to what was happening,” Shaura says. “Then one day I tried this drug, and there were no more dreams, there was no more emotion.”

“I was hooked within a month”

“It was like a comfort blanket; pure escapism. I was able to have that escapism from the whole of reality because I became consumed by this practice,” Shaura says.

“I was hooked within a month and from there it probably took me about ten years to get off it.”

Chapter 2: Consumption

Shaura’s addiction became a means of survival. The solace she found in drugs took away the angst she had always harboured and numbed the grief of losing her child. It provided an external solution to internal turmoil from which she desperately wanted detachment.

“Every day would be dictated by it. I would wake up ill – withdrawing, rattling – and immediately reach for the substance.

But the drug could only do so much; it could not give Shaura the reassurance or answers she wanted to hear or help her to overcome her grief.

It could only suspend reality.

“After about three months of living like this, I started to realise how ill I felt when I wasn’t taking the substance. I knew I had to get away," Shaura says.

Shaura went away for a week to detox from heroin. This process is intensely uncomfortable with symptoms including feverish chills, aching muscles, anxiety and insomnia.

"This drug is my go-to to stop the pain"

“I was doing my best to have the will not to go back to it, but the underlying psychological issues had not been dealt with, so it was very hard to get away from the idea that this drug is my go-to to stop the pain,” she says.

After returning from her detox, Shaura lasted a week before relapsing.

“And those urges are so unconscious. I remember not realising what was happening, almost just as I was taking the substance I was like, ‘Oh shit I’ve just done it again’”.

This cycle of detox and relapse continued on for years, over which Shaura became more disconnected from herself and farther away from being able to understand or overcome her addiction.

It never crossed her mind that she could find her way out with spiritual practice. Shaura didn’t believe in that kind of thing anyway.

But that all changed when the Road Man arrived.

Chapter 3: Ceremony

Shaura was curled up in a ball inside a willow-bark tent, heated up with volcanic rocks and steam. The Road Man – the spiritual leader of a community of Native Indian Americans – watched over her while other people chanted long, elaborate prayers to the sound of banging drums.

“It was other-worldly and beautiful, but I didn’t notice at first, I was preoccupied with my own pain,” Shaura says.

Shaura was in Oregon, USA. She had been sent there by a kind relative to spend time with her father. Here, they hoped Shaura would find what had been looking for since leaving home all those years ago.

Shaura’s father, a respected local Forrester, and step-mother sought the help of their friend, a Native Indian American woman named Theresa Takencareof, to ask if her traditional spiritual practice could be of any benefit.

Theresa believed it could. She became Shaura’s sponsor into Native American Tradition and swore to help her friend’s daughter.

"I was withdrawing as I got off the plane"

Theresa enlisted the help of the Four Nations Sundance Family. The tribe, despite having never met Shaura, came in their numbers to help her.

Together they built a sweat lodge for a purification ceremony that they believed would powerfully intervene in Shaura’s addiction.

“I was withdrawing as I got off the plane. And when we arrived the Road Man said I had to tell everyone why I was there, why I needed help,” Shaura recalls.

“There were probably fifteen people in this lodge, all crammed together on the floor. I didn’t want to speak. I was so full of shame and guilt,” she says.

But these people couldn’t pray for her without knowing why she needed it. So Shaura spoke.

“I told them that I was struggling with addiction and that I needed to be free from it.

“I curled up in on the floor, all pitiful and feeling sorry for myself. It was dark and the rocks made it hot, a bit like a sauna. People were singing and praying.

“I stayed like this for a while, then all of a sudden this thought came through my brain that told me I needed to sit up straight.”

Shaura pushed herself up from the floor, crossed her legs and straightened her spine. She breathed deeply and listened to the sounds around her. For the first time, she was using something other than drugs to alleviate her suffering.

“Sitting there, I began to sense that there was a different energy in that place. I realised I had to face it all. It was the beginning of a long road, but this experience allowed me to begin to walk back to myself.”

A few days later, Shaura was invited to take part in was an all-night Tipi meeting.

Tipi meetings are a traditional Native Indian American ceremony where people gather around a fire all night and take the cactus plant peyote. Peyote is said to trigger deep introspection and insight, and has been used in spiritual ceremonies for more than 5,000 years.

The Road Man gave Shaura a cup of peyote tea. She looked around, feeling sceptical.

“I thought it was just an excuse for everyone to get off their head,” she says.

“All this negativity came up in my mind. I was looking around at these people dressed in feathers and bright colours, people who had travelled, some from other states, to help a stranger."

"We love you because we are you"

The Road Man looked at Shaura.

He said, "Shaura, I need to tell you that we love you, and I know you probably don't believe that, but I need to tell you that we love you because we are you’.

“Even now I can feel the power of those words," Shaura says. "It was like the words I had needed to hear my whole life.”

Shaura was given a single Macaw parrot feather to hold for focus and was told to do nothing but watch the fire, still and quiet, while the peyote did its magic.

Using a psychoactive substance in a ceremony to free someone from substance abuse certainly carries a striking paradox. But, Shaura explains, the real potency of this medicine is in the intention of the user.

“When your intention in taking a drug is avoidance, to escape from reality and from yourself, it will harm you in so many ways.

“The intention here wasn’t avoidance. It was the opposite. It brought up all my emotional sickness - they actually call it 'geting well'", Shaura laughs.

"I had a purpose on this earth"

Shaura’s experience with the Native American family brought with it a revelation; she recognised all her past loneliness, recklessness and emotional pain as spiritual sickness.

“This wasn’t a religious awakening,” Shaura says. “I don't believe our innate nature as humans responds well to being told that we need a priest to talk to God for us, or what he is or isn't called.”

For Shaura, this revelation wasn’t necessarily about finding God, but finding herself – her true spirit.

“Recognising my addiction as a spiritual sickness gave me something to reach for - there was something that I needed to do. I had a purpose on this earth.”

Bolstered by that purpose, Shaura returned to the UK in search of her own spiritual path.

Here, she found yoga.

Chapter 5: Compassion

“Before I left, the Road Man told me that it was important I find a spiritual path at home – I probably owe my life to that advice,” Shaura says.

Inspired by Theresa’s daughters who had first introduced her to yoga while she was staying with them, Shaura began practicing Kundalini Yoga.

This form of yoga is an intense and transformative practice anchored in the belief that all of an individual’s potential is already inside of them.

“Yoga built upon the work that I did with the Native Americans, but also gave me something of my own,” Shaura says.

“I was beginning to make sense of my life. The philosophy it offered allowed me to develop that value system and refine it in a way that I had not been able to do before.”

Shaura would practice yoga every day, either at a local gym or with a DVD at home. She did not relapse.

“Yoga gave me something for me”

“When I walked away from addiction, I was never going back. I was clear. I was free. Yoga gave me something for me,” she says.

Shaura found love and support in her partner, Neil, and four years into her spirit-based recovery, he had some advice for her.

“He said to me, ‘I don’t know what star is above your head, but it looks to me like you’re never going to be very rich, but what you have got is your experience, and I think you’re going to find that you’ll need to go back in there and help,” Shaura says.

Shaura took his advice and after training to be a yoga teacher, she volunteered her services at an addictions support centre in Sheffield.

“I said I was a yoga teacher and that I’d had this experience with addiction. I asked if I could run relaxation sessions, and they were kind enough to let me,” Shaura says.

"Practicing yoga with Shaura has quite literally changed my life. She continually pushes her own boundaries and therefore mine also" - Gail Stephens, Yoga student

Shaura wanted to give those in her class the best support possible and began to read widely about the links between mind-body practices and mental health.

Through this, she began to understand that her powerful experience with the Native Americans could potentially be explained with science.

Enthralled, Shaura enrolled onto a professional training course for yoga therapy for mental health with the Minded Institute in London.

"She beautifully combines the philosophy of yoga with science-based principles" - Heather Mason, founder of the Minded Institute

“It’s cutting-edge yoga therapy, based in neuroscience.

“There’s a 5000 word entry paper, so I wrote my story and said I wanted to understand my experience and use it to help others,” Shaura says.

Heather Mason, the Founder of the Minded Institute, read Shaura’s paper and asked if she would continue to investigate the neurobiology of addiction, to develop a training course for yoga therapists and health workers on how to treat addiction with mind-body practice.

“I wanted to understand my experience and use it to help others”

Shaura studied hard and developed the UK’s first Yoga for Addictions training.

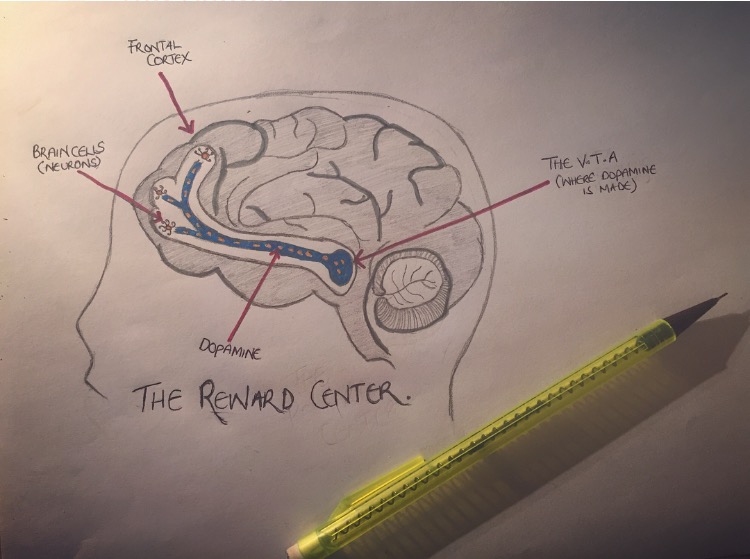

Addiction forms in the reward center of the brain. But, Shaura says, this is also where it can be combated.

Her research found that yoga practice releases feel-good chemicals such as dopamine into the brain’s reward centre, which can help fight craving.

"The release of dopamine tells the brain that this behaviour is important," Shaura says.

"Where before the addict needed a substance to have this feeling, now this practice can replace all the negative behaviours of addiction.

“Yoga engages the reward pathway so there is a high chance of it becoming a permanent fixture within the consciousness," she says.

“The practice then teaches people to self regulate, to form healthy patterns and make new networks within the nervous system, as well as forming a positive community and environment of recovery, all of which is important for the addict,” she says.

That is not to say that yoga is a drug. Shaura’s view of addiction is grounded in compassion, and yoga, she says, is a sympathetic practice that can help an addict deal with a problem in a healthy way.

“Yoga can unite the individual to their innate nature”

“People who suffer with addiction may have pre-existing existential issues, past trauma, recklessness or boundary issues,” Shaura says.

“There appears to be a sense of loneliness and separation at the heart of many addiction issues. But by setting a positive intention for the practice, by giving meaning to being able to stand in a potentially uncomfortable position for a length of time, and by inciting relaxation and calmness in the brain and body with breath practice, yoga can unite the individual to their innate nature and empower them toward recovery.”

Shaura’s course has been delivered to almost 100 therapists, psychologists, nurses and mental health professionals in the UK. She hopes that the mind-body principles it contains will reach our healthcare policymakers to create compassionate treatment for those suffering with addiction.

Shaura intends to continue to devote her life to yoga and helping those still burdened by ‘spiritual sickness’. Her journey with addiction, she says, has given her a sense purpose and compassion for herself.

“If I could go back and say something to my 16 year old self, I would tell her that she would be OK. I would say everything you need is inside yourself.

“But I also have this feeling that that aspect of my life is not one that could necessarily be changed.

"Maybe it didn’t have to happen in the extreme way that it did, but without it there wouldn’t never have been the need for me to develop this understanding, and turn it into something positive,” Shaura says.

“When I look back, I feel an overwhelming sense of gratitude. Gratitude for the people who have helped me along the way, gratitude for this yoga practice and for being able to come back to it, and myself, every day.”